I'm an army reservist. That means I'm a part-time soldier for the Canadian Armed Forces, who train constantly and volunteer to serve when there is a need to fight wildfires or deploy to a war zone.

I'm proud to be in the army and believe it's a force for good. But I've learned to keep this aspect of my identity under wraps because some people grow distant or sometimes become antagonistic and even rudely suggest I must have a taste for violence — just because I'm a soldier.

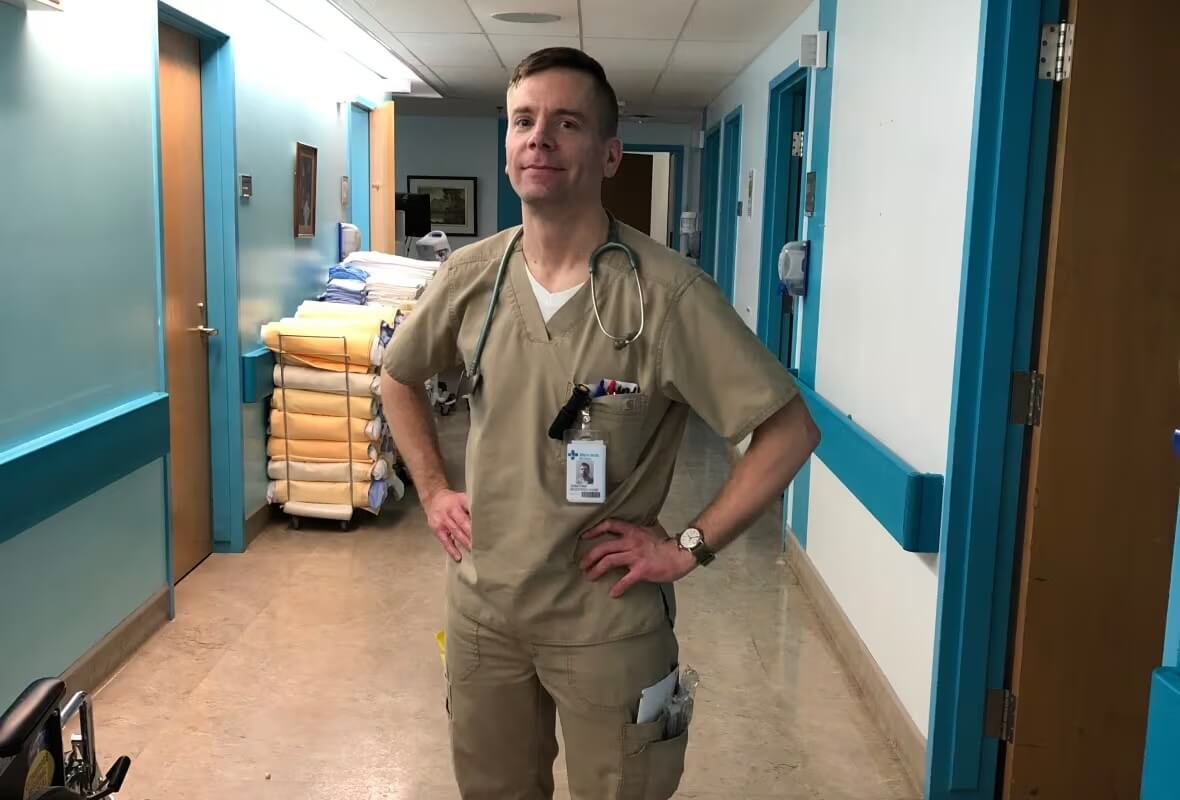

But that's a myth. If only they knew, I've seen just as many good-hearted people and as much camaraderie in the military as I have while working my other job as a critical care nurse in a busy Calgary hospital.

To be fair, I used to have my own doubts. As a child, I wondered if soldiers were automatons like Charlie Chaplin's machine men. When I joined Canada's army reserve at 19 in the 1990s, I worried it might be full of jerks and bigots. But I wanted to try something different. I wanted to get through something tough that would benefit me. I wanted to serve Canada.

Right from the start of basic training, the focus was on team-building and looking out for the buddy beside you.

My cohort was 40 men and five women, most in our early 20s, with a range of ethnicities, spoken languages and educational backgrounds. We became a tight group with friends who often felt more like brothers and sisters. In the junior ranks' mess, I hugged and was hugged by way more guys and gals than anywhere else — even when we weren't trying to "drink the fridge."

In 2003, I put my name forward for an overseas tour. My unit was deployed outside Dubai on a support base for the Canadian mission to Afghanistan. There were stressors and frictions but real bonds grew and sustained us through the boredom of security work, stupefying heat and occasional bad news from loved ones back home.

When the deployment was over, my friend Dave said that the sudden end felt like losing a job, a home and a relationship all at once, and I agreed.

Our detractors suggest we're hungry for violence. But I wasn't trained to be excited to kill and even during practice, no one demonized the potential enemy. The closest thing to that might be the nickname for the standard rifle target — an image of a charging, angry soldier we called "Herman the German." It felt like a relic from the Second World War, but didn't change after the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, when the Canadian military was sent to Afghanistan.

When I joined the military, I didn't expect to be thanked for my service. But I also didn't expect the random moments of hostility from Canadians.

I was in uniform when a smartly-dressed middle-aged woman stopped me on the street in Montreal, told me I was uneducated and doing nothing with my life. She also added, "Try not to kill anybody today."

Another stranger drove his car partway into our convoy in Vancouver and pretended to shoot me in the face. Another man in Montreal yelled at my regiment that we should shoot each other.

I shrugged it off and rationalized the vitriol as a political reaction from people who saw me as just a symbol of wars they didn't support.

Then in 2012, I went to nursing school. I learned to make a bed using hospital corners, just like in the army, and noticed other similarities, such as a commitment to serving others, working long hours while suppressing one's own needs and wants, being expected to run toward danger instead of away from it as well as trauma bonding and dark humour from shared rough experiences.

Both nurses and soldiers are highly trained workers who use their intellect and initiative constantly in daunting work. Even junior members are entrusted with great responsibility, including matters of life and death.

Despite that, I learned not to talk about the army side of me. I had too many friendly work relationships turn sour when they learned I was also a reservist. On one placement, even a supervisor, who smiled a lot and seemed to like my performance, turned cold and became critical after my manager mentioned that I was a soldier.

Unlike the strangers who came up to me on the street, slights at my work felt more personal and I learned life is easier if I hide that part of my identity. But I'm speaking out now because the military matters to me. I'm proud of the work we do to support stability on the world stage and to stand up for our allies.

Plus, I've personally known, appreciated and cared about a much larger and more diverse swath of Canadians as a result of my joining up, and I've become a more humane, more social and more open-minded person.

I hope my fellow Canadians realize their reservist service members are not so different from them. In my experience, we join because our fellow citizens and our country matter a great deal to us, and we stay because we care about our purpose and for the deep affection for the brothers and sisters we find on the inside.

Jonathan Lodge is an army reservist who has trained and led soldiers in Canada. He deployed overseas in 2003 in support of the Canadian mission to Afghanistan. He’s also a critical care nurse at a hospital in Calgary.

Jonathan wrote this story as part of the 2023/24 Veterans' Writing Workshop, and it was featured on the CBC website as part of the First Person series.